Methods

Postpedagogical case studies need methods that are sufficiently attuned to “ecologies of spaces, bodies, objects, technologies, problems, and questions,” as we put it in the Introduction. The case studies we focused on also required documenting action at different levels of scale, from the organizational work conducted by faculty; to the interactions between faculty, students, and outside experts; to students pursuing with each other the precise work of physical prototypes. In order to tune ourselves to such complex environments, it was necessary to “[shift] research from a process of problem identification and problem solving to a response to the urgency of a particular situation within which the researcher is immersed” (Fleckenstein et al. 407). We are not seeking to solve the problem of teaching in a postpedagogical moment; to think in such a way would re-constitute the problems that postpedagogy responds to in the first place. We do, however, understand ourselves to be working in a moment of urgency, grappling with what we believe teaching to be and to be capable of. This urgent moment coincides with the rise of interest in design methods within rhetoric and composition, and we initiated this research in order to explore our felt sense, our gut feelings, that design methods and postpedagogy seem to fit together and offer concrete approaches to and possibilities for teaching.

We considered methods both for our research and for the creation of this digital project. For research methods, we embraced Middleton, Hess, Endres, and Senda-Cook’s model of participatory critical rhetoric. We found especially important the notion that “[p]articipatory critical rhetoric gives critics the chance to be at the site of materializing rhetoric, and, as a result, they can experience the spontaneous and strategic (inter)actions of material bodies as rhetoric unfolds” (62). Building case studies of studio learning required being present and witnessing what materialized, including the interactions among studio participants. Attending critiques, discussing the projects with all participants, and photographing people and objects brought us into the unfolding rhetoric of the studios. Interviews especially brought us into these affective relations, as faculty discussed the highs and lows of teaching in design studios and students reflected on learning in an environment that values “productive failure,” for example. Rather than being perceived as outside observers, we instead found that participants in design studio work understood our documentation to be part of a larger whole of the action in the studio. We showed up interested in what would unfold, and what we found instead is that our work enfolded us into the ecology of design studios.

In terms of the creation of this digital project, we decided that a traditional textual narrative was not the best way to represent our research, which involved the documentation of materials, environments, and experiences. Instead, in conjunction with the Scholars’ Lab at the University of Virginia—a center that promotes collaboration among researchers, coders, and makers of all kinds—we devised this webtext. We presented a near-finished draft of our textual scholarship to the Scholars’ Lab staff and worked specifically with designer Jeremy Boggs to imagine possibilities for creating a digital version of the project. Part of the mission of the Scholars’ Lab is to work with rather than for scholars to develop projects. Boggs taught us the basics of GitHub (an open-access online code repository that neither of us had any prior experience with) and helped us come up with a functional, user-friendly, accessible design. The three of us worked together via GitHub for several months until we developed the current version of the project. We consider Boggs to be a true collaborator in this work.

We knew from the start we wanted to create a project that as much as possible conveyed the entangled action, emotion, intensity, and materiality of design practices. Responding to the postpedagogical call to design occasions or contexts, then, we built a web environment in which users can have their own experiences of the four field sites (described below). By including visual, aural, linguistic, and spatial modes of communication in the design of this webtext, we hope to represent the complexity, as well as the emergent patterns, of learning in design studios. Keeping a diverse range of users in mind, we also provide captions and alt text for the images and transcriptions for the audio embedded in this webtext. In the most ambitious sense, we hope users/readers of this webtext will begin to identify with the places, people, and rhythms of our field sites and, as a result, craft their own innovative learning environments.

Field Sites

Over the 2015-2016 academic year, we set out to explore how design pedagogy operates in a variety of classrooms, from STEM programs to art and architecture schools. By selecting sites of study in design-oriented classes, we were able to observe first-hand how these teaching and learning practices can inform rhetoric and composition, as well as initiate mutually-reinforcing pathways within and between STEM, design, and humanities teaching practices. We visited what we felt were some of the most interesting classrooms and programs in the Baltimore/Washington, D.C. region. To provide some context, here we include thumbnail sketches of our primary research sites. We chose these sites in particular because they illustrate what we have identified as the four salient features of design approaches—High Impact, Collaboration, DIY, and Ecological—in coordination with each other, not as separable teaching methods. This coordination is key to developing a productive model of complexity for postpedagogy.

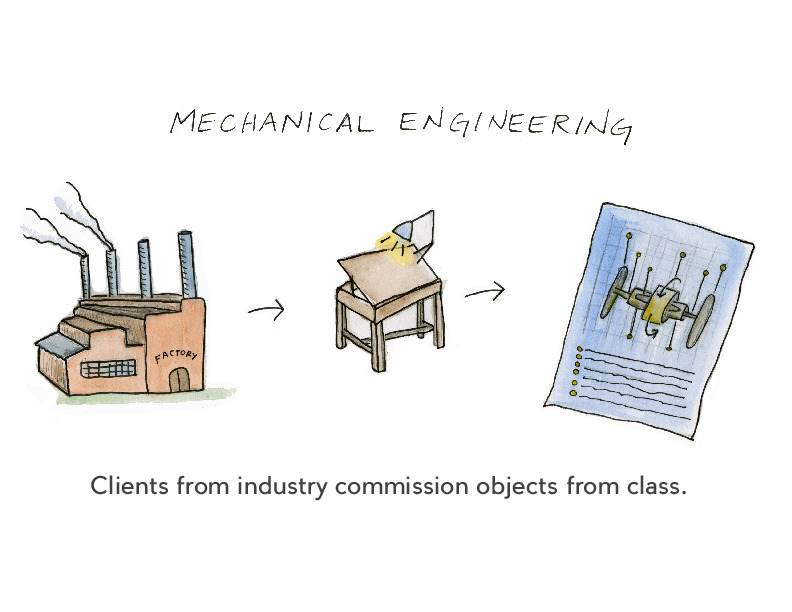

Mechanical Engineering Capstone Seminar, University of Maryland, Baltimore County

This intensive seminar, led by Neil Rothman, is a graduation requirement geared toward teaching students to engage in the kind of collaborative problem-solving they will encounter on the job. The seminar covers topics such as the “design of components that form a complete working system; engineering economics, performance-cost studies, optimization, engineering design practice through case studies; and legal and ethical responsibility of the designer” (“Mechanical Engineering”). What we found most compelling about the course, however, is the fact that student groups are hired by real clients to create specific material products. They are given a limited amount of funding to complete their projects, and they must deliver a fully-designed prototype by the end of the semester. We were given permission to observe students early in the design process, at classroom presentations with clients in attendance, and at a showcase where they demonstrated their final designs. In addition to documenting the mid-term presentations student teams made to their clients, we also took photos of a semester-end poster session and interviewed Rothman at length.

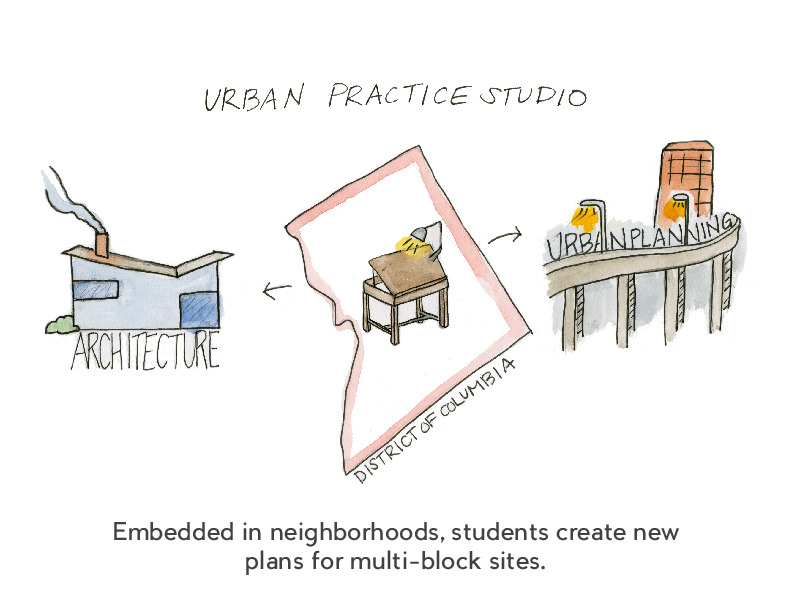

Urban Practice Studio, Catholic University

In Eric Jenkins’ studio, which fuses architecture and urban planning, student groups practice “urban design as a civic art and interaction of the physical, historical, theoretical, moral and ethical fabric that impacts and shapes communities” (“Urban Practice”). In the sessions we observed, students worked on collaborative projects to redesign an existing area of D.C.—Union Market—with the aim of revitalizing it as a space that would better suit community needs and values. In midterm and final critiques (“crits”), we observed students present, discuss, and defend their work to a panel of local urban planners, architects, and business owners. At this site visit, we attended mid-term and semester-end critiques and took photos of these events, students, posters, and models.

LEEDlab, Catholic University

Patricia Andrasik, assistant professor and head of sustainability outreach at the School of Architecture and Planning, describes the LEEDlab as an integrated, interdisciplinary lab course that focuses on action research—a course that lives in CUA’s architecture curricula but calls on sustainability studies at least as much as architecture. According to the LEEDlab website, “The course is a laboratory for students to experiment with various quantifiable synergies and policy revisions in order to reach the most optimal sustainable goals towards certifying existing campus facilities through direct collaboration between students, faculty and a third party green organization” (“LEEDlab”). Notable for our purposes are the ways that students work in teams, initiate and lead projects independently, and coordinate with facilities management on campus in order to achieve implementation of significant changes to the environmental systems on campus (power, water, air quality, and the like). At the LEEDlab, we attended a mid-term “eco-charrette,” where student teams met with staff from Facilities and Custodial Services to discuss project frames, research, and future work. Following the eco-charrette, where we collected materials and photos of the meetings, we also interviewed students.

Studio Collaborative, Georgetown University

In the spring semester of 2016, Matthew Pavesich and a team of others at Georgetown University ran what they called the Studio Collaborative. The Studio Collaborative, housed in the Kennedy Institute of Ethics and its EthicsLab, is an ongoing pilot project that brings together courses in science, policy, ethics, and rhetoric. Student teams with members from each class conduct their coursework in a design studio. As stated in the Collaborative’s course materials, “The experiment, which is part of Georgetown’s Red House Initiative, is based on the idea that deeper learning occurs when students from different disciplines collaborate with each other on authentic projects aimed at making real-world change” (Dhillon et al. 1). The aim of this specific experiment is to learn together “by connecting sets of courses that share fundamental issues . . . we can create a multiplier effect that will exceed the effect of stand-alone classes” (Dhillon et al. 1). From this site, Pavesich contributed artifacts from the courses and their crits, and interviewed Arjun Dhillon, head of studio at EthicsLab.

Frames-for-Work

At every studio we visited, there were strategically designed, complex learning environments, or what we are calling “frames-for-work.” Instead of prescribing what and how students learn, studio faculty assembled constellations of “tools, raw materials, spaces, media, and people” and set students loose (Sheridan “A Maker Mentality”). Similarly, Byron Hawk has written of the need to “build smarter environments in which . . . students work . . . [We must create] constellations of architectures, technologies, texts, bodies, histories, heuristics, enactments, and desires that produce the conditions of possibility for emergence, for invention (249). These frames-for-work enable invention, which involves connecting students with knowledge, material, and spaces that can facilitate their thinking and making practices.

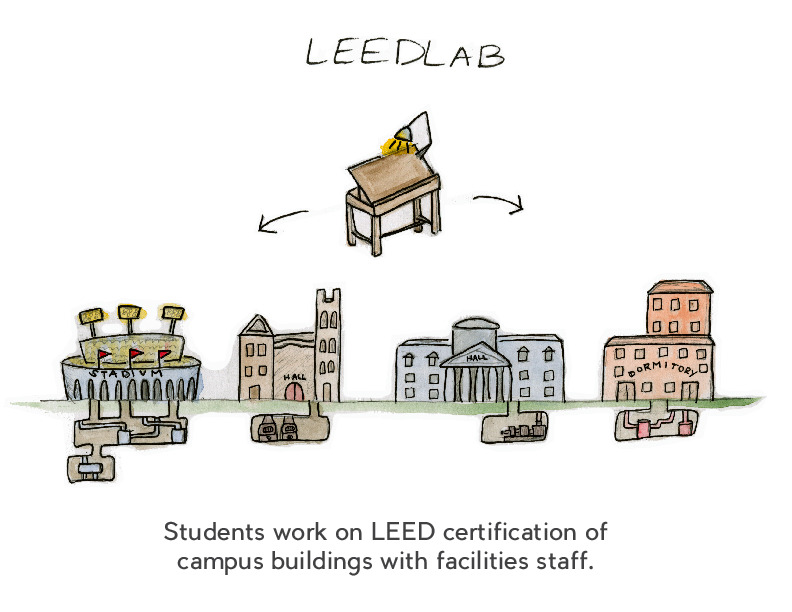

[Note: We collaborated with artist Katherine Noland to imagine sketches of the “frames-for-work” for each of our field sites. After discussing the sites and our aesthetic preferences, Noland composed these images that combine sketching with watercolors.]

The environments represented in the sketches we include above all share certain qualities. First, students are asked to work on issues that are extremely complicated; learning-oriented design studios double down on this complexity by requiring students to engage in multiple processes and to work in fluid team arrangements at different levels of scale. Second, these design studios have a distinct ethos, or what might be described as a “can-do” attitude that is both serious-minded and fun at the same time. Third, in these environments students are cautioned against committing to any one path as they proceed with their project. This intentional ambiguity, underscored by rapid prototyping and iteration, keeps open the possibility of successful experimentation, but also the well-known “productive failure” mentality of design methods, or when students learn “how to assimilate [failure] and to use it to move forward” (Farson 187). Lastly, these frames-for-work seem to encourage students to merge the creative with the critical. By collaborating, facing complex problems, and conducting deliberate, self-driven research, students gravitate towards inventive solutions using grounded critical thinking to reach potentially powerful ends.

The Contagious Spirit of Design

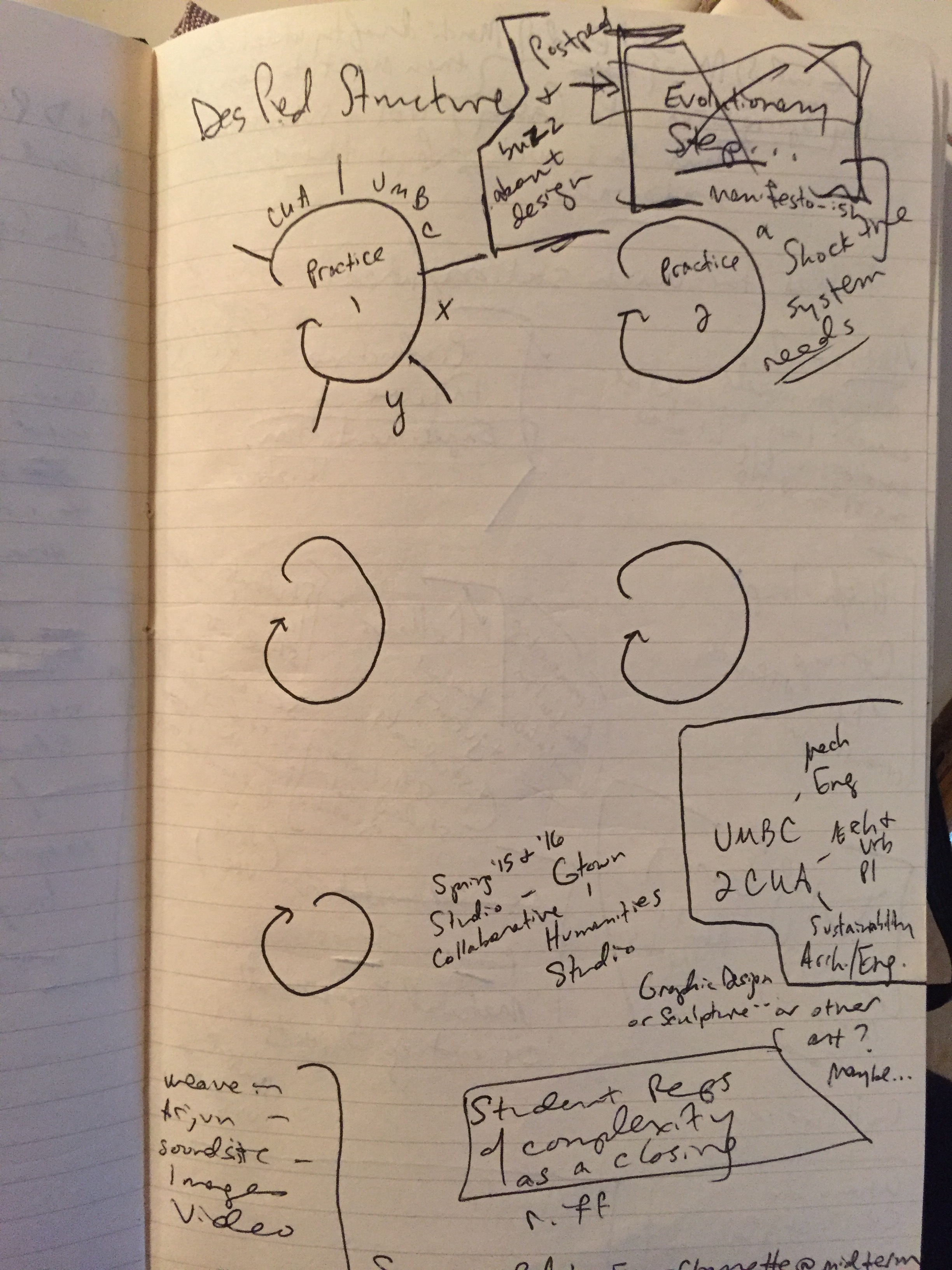

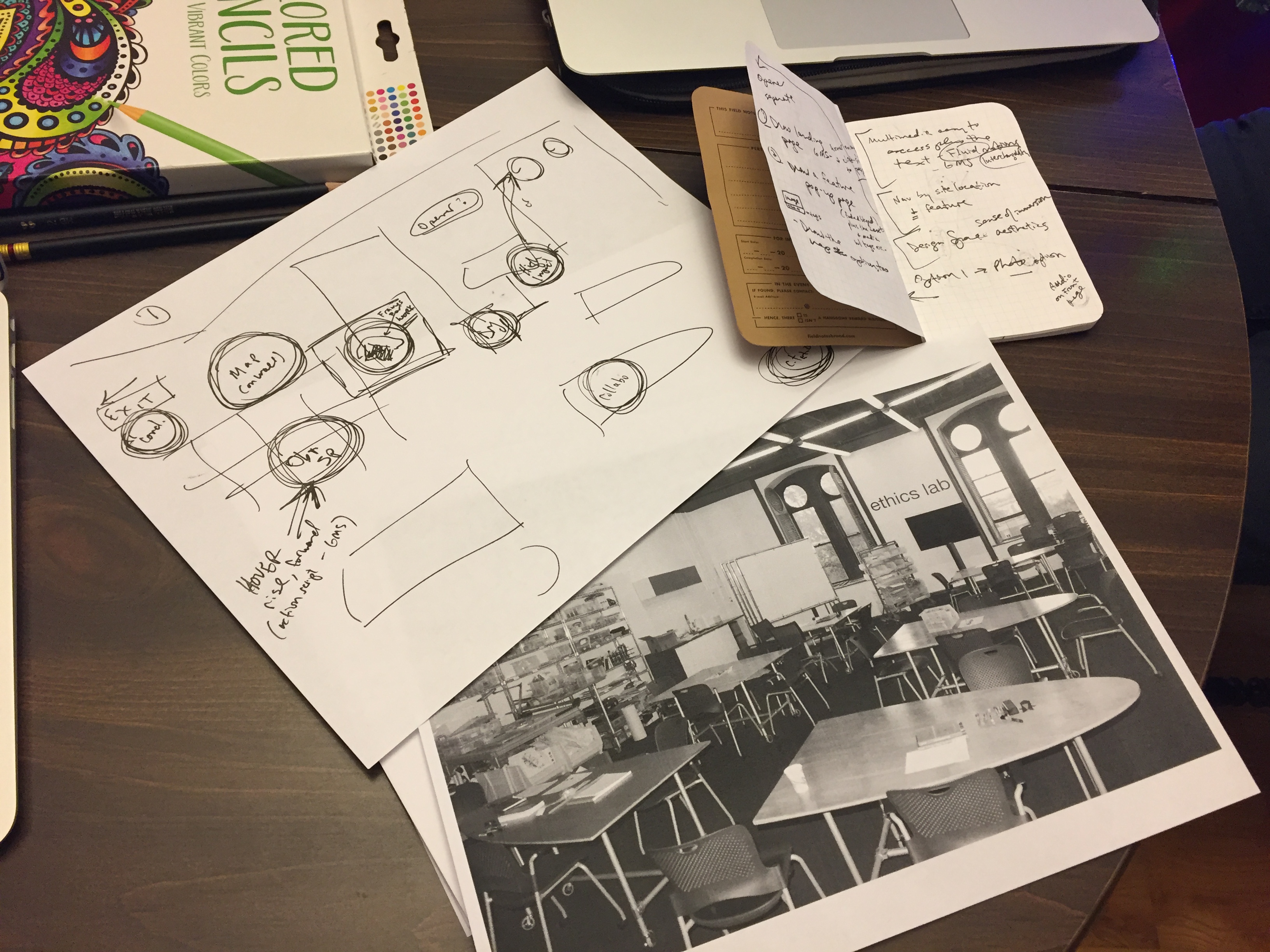

Before, during, and after our visits to these sites, we made a conscious decision to adopt the spirit of design approaches by embracing uncertainty, trial and error, and experimentation in our research methods. In fact, we ended up internalizing the practices we witnessed in the classrooms we observed. For example, we drafted many preliminary sketches to try to visualize possible variations of our project’s form and structure—to imagine and reimagine how our research might be represented.

These drawing sessions allowed us to envision our project as a material thing with complex working parts; they provided an opportunity to explore a multitude of possibilities—often with other people—before deciding on a cohesive concept for our project. Additionally, we relied on DIY methods like iPhone photography and rough audio recordings to capture sights and sounds from the scenes of learning in which we were immersed.

In the version of our project that we share here, we discuss the most salient design practices that emerged during our observations—High Impact, Collaborative, DIY, and Ecological. Each feature’s page contains a curatorial text in which we define key terms, present artifacts (e.g. images, audio, teaching materials) from our fieldwork, offer general commentary, and make connections between what we observed and relevant research in rhetoric and composition (and elsewhere). As we will show, it is the coordination of these features that is essential to crafting impactful learning experiences for students.