Design studio methods are grounded in embodied interactions with material objects and innovative learning spaces. This feature of design programs has begun to spread beyond studio settings. Many forward-thinking workplaces and sites of higher education are investing massive amounts of money to enhance the physical conditions of living and learning (Lange). Attention to the material nature of learning is not new to rhetoric and composition either. Numerous scholars have called our attention to the material and ecological aspects of composing, both inside and outside of the classroom (Cooper, Hawk, Dobrin, Rickert, Haas, Syverson, Rivers and Weber). As Laura Micciche argues in “Writing Material,” our approaches to teaching should reflect that “[w]riting is codependent with things, people, places, and all sorts of others. To write is to be part of the world” (501). “Designing,” as we will demonstrate, could easily be substituted for “writing” in Micciche’s statement. We believe that the heightened and sustained attention to physical learning spaces and embodied interactions with material things demonstrated in design studio settings can further enhance postpedagogical practices. In fact, the following discussion amplifes how Santos and Leahy’s characterization of postpedagogues as “architects” of learning experiences means attending to both conceptual and material conditions for learning.

The media and materials we collected during our studio visits illuminate the myriad ways objects significantly figure into design approaches to teaching and learning. For example, many of the students we observed were commissioned to produce objects, such as this orange plastic cylinder created by a student team of UMBC mechanical engineers.

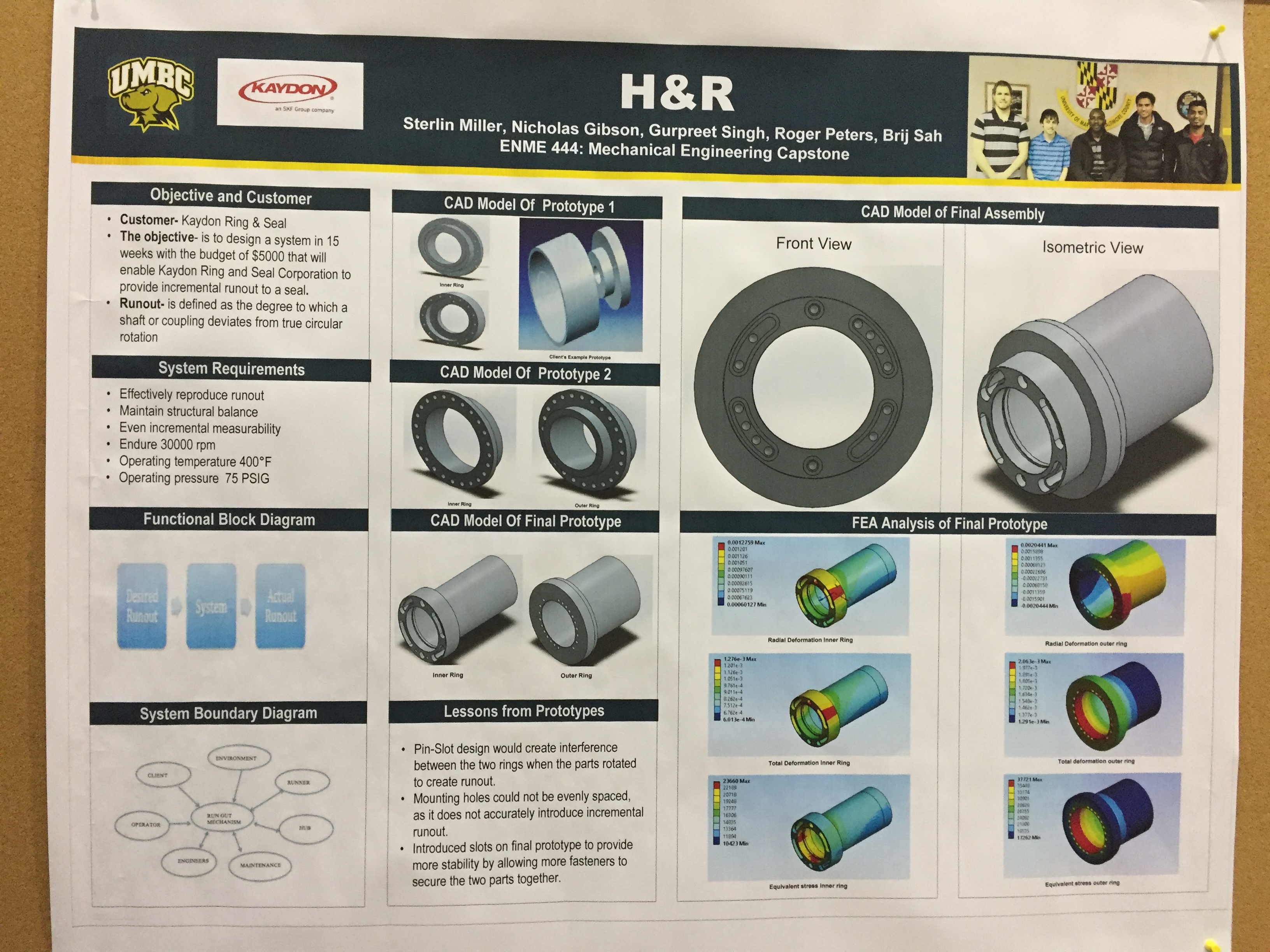

This object is a prototype of a seal that will provide incremental runout (as illustrated in the poster shown later in this section). The seal was commissioned by a client in private industry in order to improve existing production processes.

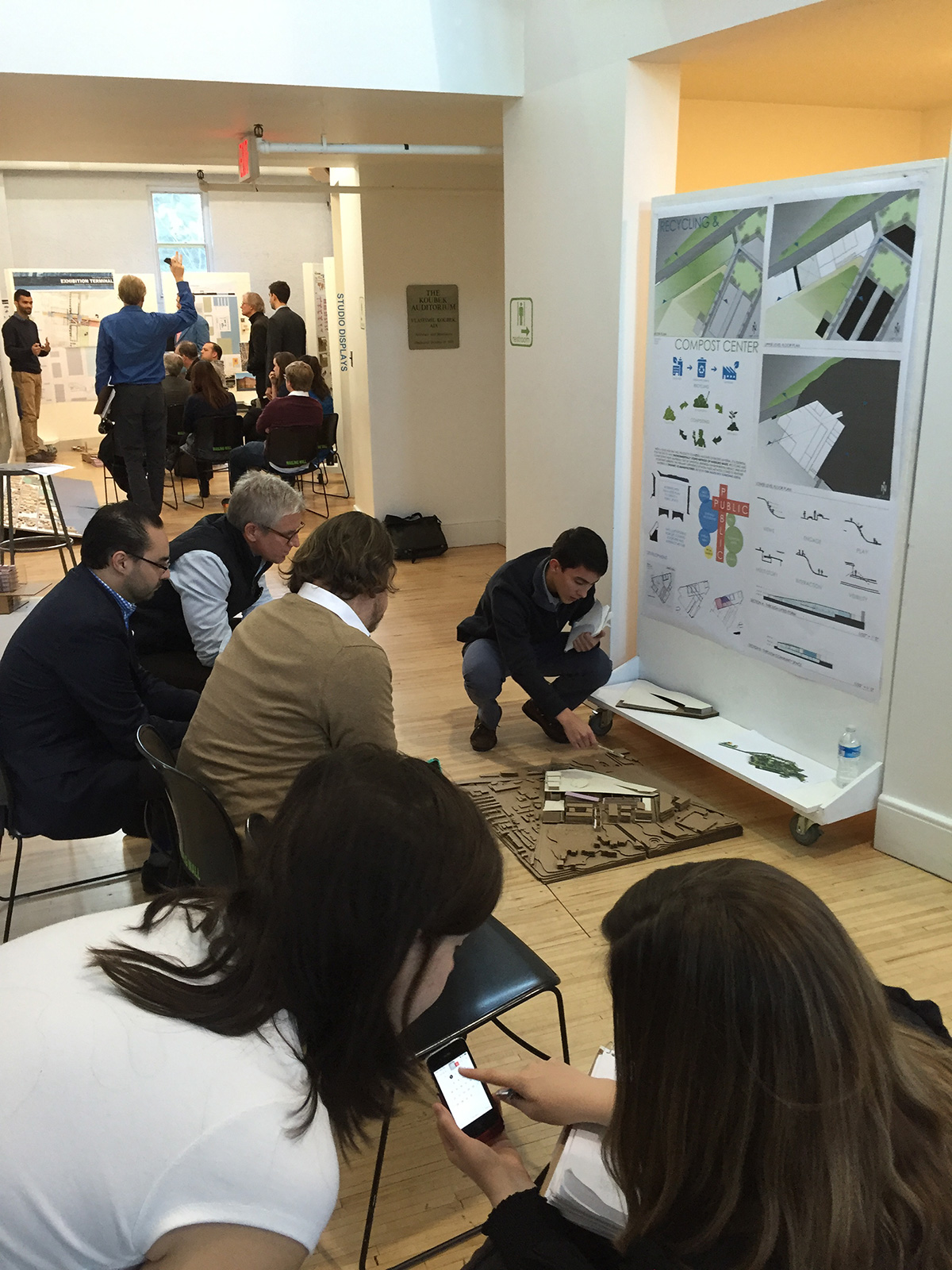

In addition to creating prototypes, design students are often expected to make material models in multiple modes. This image depicts a model of a reimagined Washington, DC location created by a team of students at Catholic’s Urban Practice Studio.

It is important to acknowledge that students do not only make prototypes or models; they must also be able to explain their making process in detail, as well as discuss the function and value of the thing they made (a metacognitive process that echoes our earlier discussions of reflection in postpedagogical and design studio contexts). Arjun Dhillon describes:

This next image, for instance, shows a student at the Urban Practice Studio translating his model to an audience external to the class (in this case, actual urban designers who work in the D.C. area).

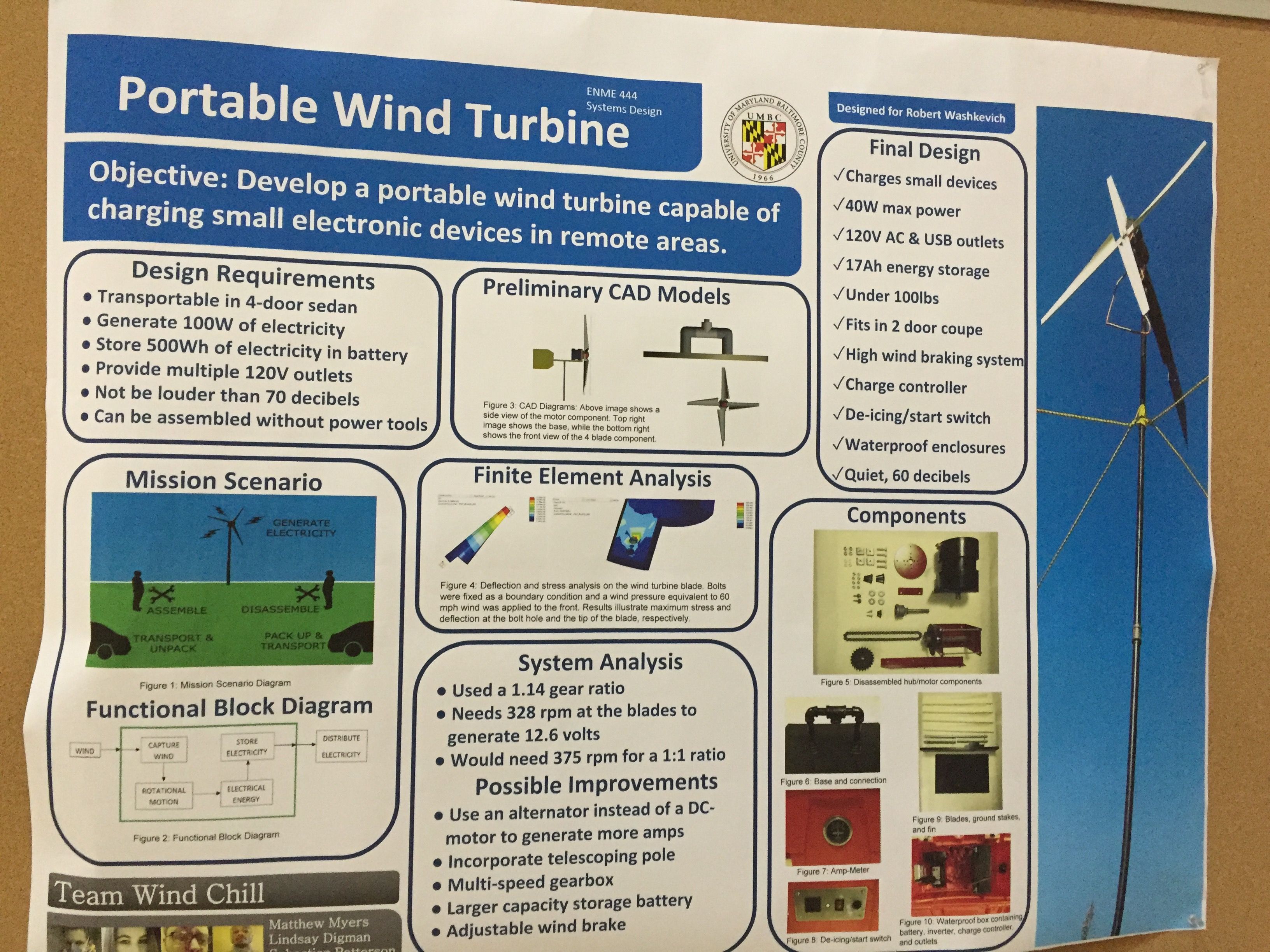

While oral presentation is an important aspect of being able to explain objects and models, students are sometimes asked to explain them through detailed posters with text and images. The posters featured below are from a final public exhibit in Rothman’s capstone mechanical engineering course at UMBC. These posters make evident the complexity involved in both reflecting on and describing the entire making process to a specific audience (e.g. clients, as well as faculty and students from the engineering school).

What we found most interesting in our observations of design studio students’ making practices was the different types of multimodalities students used to enhance their learning. As we witnessed, students worked with a range of alphanumeric texts (digital and otherwise), illustrations, objects, and models. It was clear that this material, hands-on approach was vital to both the design work they were asked to do and to their learning processes.

However, having students create and engage with materials and models is not enough to help them become designers. As Dhillon stated in his interview, teachers must provide the context to help students become designers.

In part, this context is achieved through immersing students in spaces where experimentation, making, and inquiry is encouraged. For example, consider the following spaces:

When we entered these environments, even as observers, we felt inspired and excited. The ways that these studio spaces were designed—innovative architectural features, large open spaces ideal for collaboration and smaller closed off spaces for individuals or small group meetings, displays of current and previous student work, blank walls for students to hang drawings and plans, huge bins of supplies and materials for making—incite the kind of creativity and desire to learn that, in an ideal world, all students should feel in educational settings.

Moreover, the spaces of the design studios we visited seemed to foster particular kinds of practices and habits of mind, such as observation, exploration, collaboration, and a sense of personal responsibility for learning. Because of the openness of the Urban Practice Studio (a renovated gymnasium), for instance, students from different classes would often wander into other students’ workspaces or class presentations. In this audio note, Ceraso notices how a student who was not associated with the crit she was observing decided to participate in an unprompted way:

Such spaces, then, allow for learning to take place outside of a singular classroom unit run by a professor. They also help make possible the practices and habits of mind mentioned above. At the Urban Practice Studio students at different levels of the program were free to roam and learn from their peers during class sessions and any time—day or night—there was something happening in the dynamic studio space. We might say that the publicness of high impact teaching practices merges in design spaces with the material ecology.

We do not mean to suggest that all learning environments must have impressive (and expensive) spaces or access to top of the line technologies in order to be effective. For instance, one could make a writing course more ecologically-attuned, arguably, by holding it in a space more public than a closed-door classroom (e.g. a shared space on campus, a museum, a park, etc.), or by providing times/spaces in which students from different classes or levels could interact. What the design studios we visited make clear is that it is an entire ecology—the hands-on making of texts and objects, the inspired spaces that encourage collaboration and creativity, and the habits of mind that emerge from these making practices and spaces—that contributes to the experience of learning. Rather than isolating the activities and features of our learning environments, it is necessary to approach our classrooms as expansive ecologies. We must consider how to coordinate the network of materials, spaces, people, technologies, and ideas to craft meaningful and impactful learning experiences.